In 1969, the American poet and interdisciplinary artist Hannah Wiener asked a question that feels even more relevant today: “The information available has more than doubled since World War II. In the next ten years it will double again. How do we deal with it?”

At that time, humanity had only just started exploring the transformative potential of technology, with humans setting foot on the moon and the birth of the internet. Technology was beginning to infiltrate everyday existence at the most fundamental level. Meanwhile information began to assume a life of its own, reshaping everything from personal interactions to global politics.

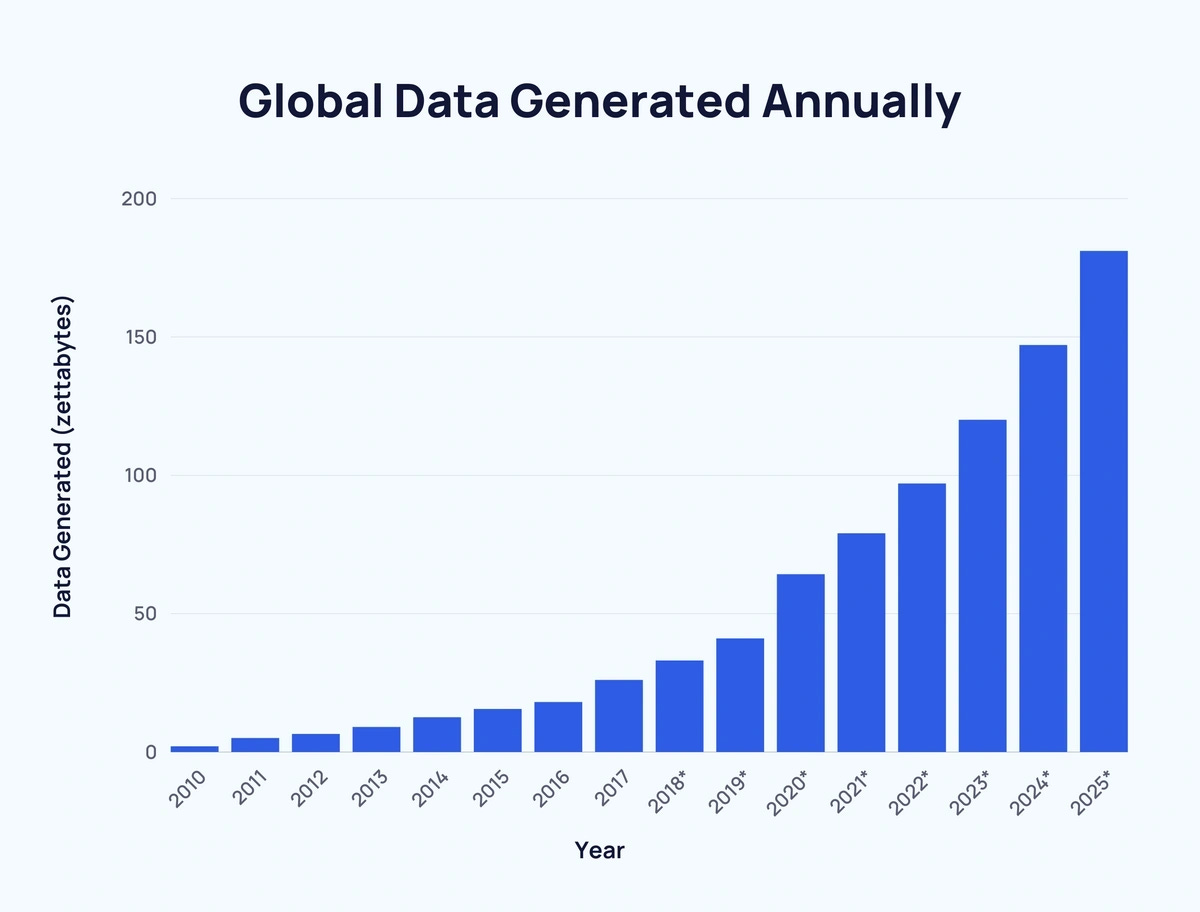

Humans could no longer live without creating data and the data that they were generated begged to be used or, more ominously, ‘captured’. The amount of data created in the 21st century has grown at an astounding rate:

In 2010, approximately 2 zettabytes of data were generated globally[1]. By 2023, this figure had increased to an estimated 120 zettabytes. Projections suggest that by 2025, global data creation will reach 181 zettabytes, A 74-fold increase in just 15 years. (Duarte, 2024) This growth far exceeds the doubling Wiener anticipated and highlights a pressing challenge: how can societies adapt to this overwhelming flow of information?

Cybernetics and Societal Adaptation

In the mid-20th century, Norbert Wiener, known as the father of cybernetics, recognized that the rapid increase in information production and dissemination was fundamentally changing how society functions. He argued that to deal with this new reality, society needed to adapt by becoming self-regulating. Just as living organisms use feedback mechanisms to maintain a stable internal environment, (homeostasis), Wiener suggested that societies use information feedback to regulate themselves and adapt to rapid social, economic or political changes.

In Wiener's model information flows in loops. Public opinion influences behaviour: governments, institutions and corporations adjust their policies in response, which in turn, shape public opinion. It is a self-regulating system, where information acts as both input and output in a feedback loop that helps societies adapt to economic, social, and political changes. Today, this concept underpins everything from public health strategies to digital content curation, offering a way to see society as a complex, responsive system.

Case in Point: The COVID-19 Pandemic

Wiener’s theory became especially visible during the COVID-19 pandemic. Governments worldwide collected massive amounts of data on infection rates, hospitalizations, and vaccination rollouts. This data functioned as a feedback loop, guiding health decisions like lockdowns, mask mandates or vaccination campaigns. By adapting policies based on real-time data, governments could regulate the impact of the virus, optimize responses and make decisions that could save lives and minimize disruption.

The Rise of Information as Power

In today’s world, controlling information flow and shaping public discourse has become one of the greatest assets of power. Those who control information-tech giants and government bodies- have come to possess unprecedented influence to shape public perception and guide behaviours.

Take the case of big data and surveillance. Through complex algorithms, corporations and governments can control what we see online, subtly steering consumer behaviour, even political opinions and economic trends. Similarly, social media platforms use algorithms to curate our feeds, amplifying certain voices while suppressing others. This ‘invisible hand’ influence public discourse, impacts elections, and steers individual behaviour in directions we may not have previously thought or noticed.

The link between knowledge and power is evident across various fields, from information technology, media and education. The digital age has both democratized access to information and centralized control, sparking debates about privacy, surveillance, and the widening digital divide. In education, for instance, curricula often reflect and reinforce societal power structures, legitimising certain perspectives while excluding others. This positions education at a critical intersection of power and knowledge, with far-reaching implications for social equity and justice.

The centralisation of information control impacts individual autonomy, trust in institutions, and the resilience of entire systems, making them more vulnerable to failures or malicious attacks. This centralization also worsens inequality, especially for those without the resources or knowledge to access vital information, thereby deepening echo-chambers and increasing societal polarisation.

Open Work and User Agency

While Wiener emphasised on ‘predictability’, ‘self-regulation’ and ‘control’ as a means to minimise human error and maximize efficiency, Umberto Eco preferred ‘ambiguity, interpretation, and indeterminacy.’ In his concept of ‘Open Works’ (Opera Aperta), which originally applied to art and literature, Eco offered an alternative - or perhaps complementary- perspective to cybernetics: technologies evolve beyond their original design through user interpretation and innovation. This means that the impact and purpose of technology are not predetermined at its inception, but rather evolve and gain new meanings and applications, often diverging substantially from the inventor's intent, through their interaction with users and society.

Take the internet, for example. Once designed for military communication, it has evolved into a global platform for commerce, social interaction, and information sharing. Similarly, smartphones, initially designed for communication, they have now become multifunctional tools for photography, navigation, health and sleep monitoring, and more. In line with Eco’s theory, rather than maintaining control, these systems thrive on adaptability and reinterpretation, continually offering new meanings of use. (Eco, 1989)

The most recent and perhaps the most visible example is social media. Facebook, X, and Instagram were originally designed as networking platforms, but have now transformed into tools for citizen journalism, political campaigning, and real-time news dissemination. Social media platforms influence political discourse, spark movements—as seen during Egypt’s 2011 revolution—and fundamentally alter how information (and misinformation) spreads.

For businesses, social media has transformed marketing, providing dynamic, interactive channels to connect with their customers. Facebook and Instagram are established advertising hubs while TikTok has emerged as a key marketing platform, particularly among Gen Z. However, their addictive nature has raised concerns about its impact on young people’s mental health and social development.

The illusion of control

In the late 18th century Jeremy Bentham introduced the concept of Panopticon, an architectural design for a prison where a single guard could observe all inmates without them knowing whether they are being watched. This ‘invisible surveillance’ created a self-regulated environment where Inmates internalised the sense of being watched, thereby adjusting their behaviour to conform to expected norms.

Digital reconstruction by Myles Zhang of how Jeremy Bentham’s panopticon would have appeared if built.Note Source: Wikipedia

French philosopher Michel Foucault expanded on Bentham’s ideas, framing the Panopticon as a symbol of how modern societies use surveillance and knowledge as tools of power. In today’s digital age, where every click, post, and interaction is subject to potential scrutiny, the Panopticon has taken on new, less tangible forms. Like inmates in the Panopticon, modern users of digital systems often adjust their behaviour in response to the awareness of observation or to avoid the social and reputational consequences of cancelation. This phenomenon cultivates a sense of control among system owners—a belief that surveillance equals power.

However, this is largely an illusion. The reality is far messier. Although centralised data and planned systems appear to shape our world, true control often eludes even the most sophisticated systems. Society, with its ever-evolving complexities, does not always respond predictably to planned interventions. Social change, for instance, is more often a result of grassroots movements, individual actions, and the unintended consequences of innovation rather than deliberate design by institutions.

The reality is that we live in a world shaped by biases, competing interests, and incomplete understanding. Innovations frequently stem from decentralized, bottom-up processes, where serendipity plays as much of a role as careful planning. The success of modern technology and governance often lies not in attempts to control outcomes but in adaptability and resilience in the face of uncertainty.

In navigating this new world, we must balance the need for order and predictability with an openness to the unknown. Errors should not be seen solely as failures but as opportunities for learning and adaptation. Personal experiences often underscore this lesson. I have encountered moments when my mistakes revealed the true nature of relationships and the unexpected generosity of those willing to forgive them. Such moments remind us that true growth and understanding often come not from controlling every variable but from acknowledging and learning from what we cannot foresee.

Ultimately, the real power lies not in control, but in humility and the capacity to embrace and learn from uncertainty in an interconnected world.

Sources and References:

Duarte, F. (2024, June 13). Amount of Data Created Daily (2024). Retrieved from Exploding Topics: https://explodingtopics.com/blog/data-generated-per-day

Norbert Wiener: Cybernetics or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine, 2019, MIT Press

Umberto Eco, The Open Work, 1989, Harvard University Press

Michel Foucault, Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972-1977, 1980, Vintage

Notes

[1] A single zettabyte contains one sextillion bytes, or one billion terabytes. Or a zettabyte is 1021 or 1,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 bytes.