Eunice Newton Foote, Drawing by Carlyn Iverson, (NOAA Climate)

Eunice Newton Foote (1819 -1888) was born Eunice Newton on a farm in Connecticut. She attended the Troy Female Seminary, which was established in 1821 by Emma Hart Willard in Troy, New York. At the time, women were barred from colleges and the Troy Seminary was the first institution in the United States that provided women with an education comparable to that of college-educated men.

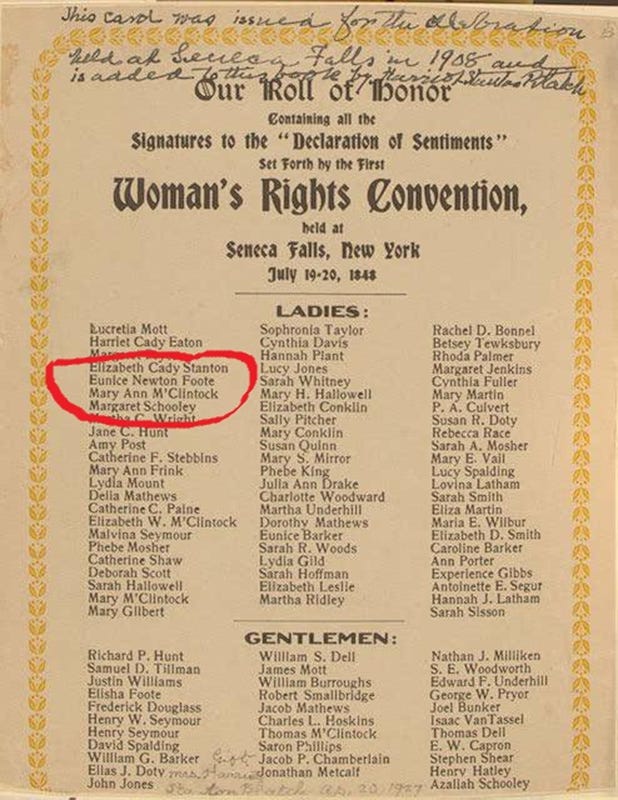

Foote was an amateur scientist, inventor, and a women’s right activist.[1] She played an important role in the 19th century women’s movement. In 1848 she attended the first Woman’s Rights Convention in Seneca Falls, New York and signed with 67 other women and 32 men, the Declaration of Sentiments in support of its principles of equality for women in all spheres of life. Eunice Foote was also the first scientist to demonstrate how different proportions of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere would change its temperature and cause significant global warming.

Signers of the Declaration of Sentiments at Seneca Falls in order with Eunice Newton Foote name firth from the top. (Wiki)

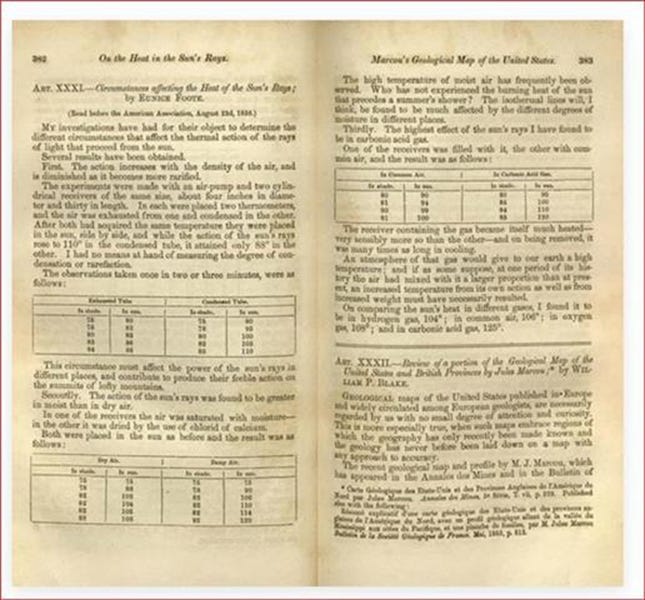

On the morning of August 23, 1856, hundreds of men of science, met in Albany, New York, for the Eighth Annual Meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) to discuss advances in their respective fields and explore new areas of research. One of the reports to be presented was titled ‘Circumstances Affecting the Heat of Sun’s Rays’, and to everyone’s astonishment, the author was a woman, Eunice N. Foote. Being a woman, Foote was not allowed to present her paper herself. Instead, a male scientist, Joseph Henry of the Smithsonian Institution, read it on her behalf. Neither her paper nor Henry’s presentation were included in the conference proceedings, but it was published later the same year in its entirety in The American Journal of Art Science (Volume 22), as ‘Circumstances Affecting the Heat of the Sun’s Rays.’ Even then, it went unremarked.

Eunice Foot’s paper ‘Circumstances affecting the heat of the Sun’s rays’ that appeared in the American Journal of Science and Arts in 1856. (Royal Society)

A summary of Foote’s was reported by David A. Wells in the 1857 volume of his Annual of Scientific Discovery. He writes,

“Prof. Henry then read a paper by Mrs. Eunice Foote, prefacing it with a few words, to the effect that science was of no country and of no sex. The sphere of woman embraces not only the beautiful and the useful, but the true.

Mrs. Foote had determined, first, that the action of the rays increases with the density of the air. She has taken two glass cylinders of the same size, containing thermometers. Into one the air was condensed, and from the other air was exhausted. When they were of the same temperature the cylinders were placed side by side in the sun, and the thermometers in the condensed air rose more than twenty degrees higher than those in the rarified air. This effect of rarefaction [the reduction of an item’s density] must contribute to produce the feebleness of heating power in the sun’s rays on the summits of lofty mountains. Secondly, the effect of the sun’s rays is greater in moist than in dry air. In one cylinder the air was saturated with moisture, in the other dried with chloride of lime; both were placed in the sun, and a difference of about twelve degrees was observed. This high temperature of sunshine in moist air is frequently noticed; for instance, in the intervals between summer showers. The isothermal lines on the earth’s surface are doubtless affected by the moisture of the air giving power to the sun, as well as by the temperature of the ocean yielding the moisture.

Thirdly, a high effect of the sun’s rays is produced in carbonic acid gas. One receiver being filled with carbonic acid, the other with common air, the temperature of the gas in the sun was raised twenty degrees above that of the air. The receiver containing the gas became very sensibly hotter than the other, and was much longer in cooling. An atmosphere of that gas would give to our earth a much higher temperature; and if there once was, as some suppose, a larger proportion of that gas in the air, an increased temperature must have accompanied it, both from the nature of the gas and the increased density (Wells, 1857, pp. 159-160).

Eunice Foote’s discovery has been lost and forgotten for about 150 years. It might have remained lost if it wasn’t for Raymond Sorenson, a geologist who collected old copies of the Annual of Scientific Discovery. He stumbled upon Henry’s presentation in the 1857 volume and immediately realised the significance of Foote’s discovery. His subsequent article on Eunice Foote, published in 2011, received a lot of attention from both scientists and historians. It also brought up another issue. Had John Tyndall's or any of the subsequent scientists, like Svante Arrhenius and Thomas Chrowder Chamberlin, read Eunice Foote’s work?

Tyndall’s biographer Ronald Jackson says that it seems “unlikely that he [Tyndall] had noticed Foote’s paper and suppressed or ‘stole’ it,” … because, “it doesn’t fit with his character, and would also have been extremely risky. Questions of priority were strongly contested, and Tyndall championed underdogs.” It’s possible. Scientific communication across the Atlantic in the mid-19th century was scarce, and it was heavily based on personal relationships, that is between men scientists. It’s also possible that he knew of Foote’s paper and ignored it. Unlike Tyndall, Eunice Foote was an amateur scientist and a woman, and her experiment, although ingenious, it was simple and homemade. Two glass tubes filled with different gases where she could compare their thermal responses to sunlight and record their temperatures rises. Tyndall’s experiments, on the other hand, were well-designed and precise and provided him with sound evidence to support his hypothesis.

Nevertheless, Foote’s hypothesis was remarkably prescient, and she has been to first person to have been experimented on warming effect of sunlight on gases and make the direct link between carbon dioxide and the earth’s climate. And for that she deserves proper recognition. We can only imagine what this woman would have succeeded if she was able to have Tyndall’s rigorous scientific training.

[1] in the 1860s Eunice Foote had filed a patent under her own name for a "filling for soles of boots and shoes" made of "one piece, of vulcanised India-rubber" to "prevent the squeaking of boots and shoes."

Sources and References:

Jackson, R. (2019, February 13). Eunice Foote, John Tyndall and a question of priority. (Royal Society)

Sorenson, R. (2011). Eunice Foote’s pioneering research on CO2 and climate warming. (Search and Discovery)

Wells, D. A. (1857). Heat of the Sun's Rays (Annual of Scientific Discovery, 159-161)