"From an altitude high in the clear stratosphere, will come pictures of storms raging far if not near"

Observing the Earth from space

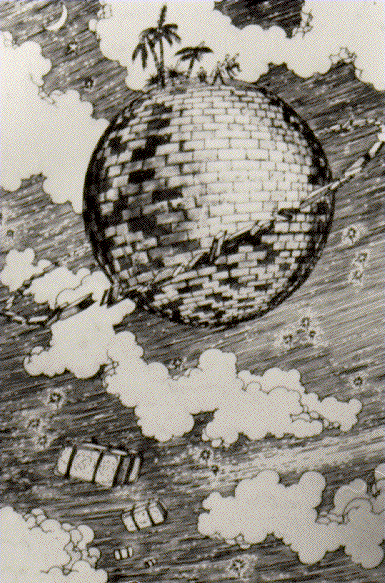

In October 1869, American Unitarian minister and writer Edward Everett Hale began serializing his novella "The Brick Moon" in The Atlantic Monthly. What is interesting about this work of speculative fiction is that it contains the first known depiction of the launch of an artificial satellite. The tale is about a group of people who build a giant hollow sphere made of bricks and launch it – with people on board- into space.

Hale, a prolific and versatile author, envisioned that the space settlers could communicate with the Earth and that a brick moon would serve as a navigational aid for ships at sea, turning this way, his imaginary space station, into a communication satellite.

There is plenty of outright magic that makes life livable on the surface of the Brick Moon. The Brick Lunarians are in fact alive at 5,109 miles above the Earth's surface. That is in the Exosphere, the final layer of Earth's atmosphere, essentially outer space. On their 200-foot diameter moon, they can stroll from summer to winter whenever they choose. They create their own soil and cultivate as much food as they and their animals need. The Brick Moon is not an exciting story to read and given what we now know about space, it is preposterous, but the fact that someone wrote a story about getting into space, in 1870, is truly incredible.

The story also explores the consequences of technological advancement and ends with a contemplation of what the ideal human society means:

“Can it be possible that all human sympathies can thrive, and all human powers be exercised, and all human joys increase, if we live with all our might with the thirty or forty people next to us, telegraphing kindly to all other people, to be sure? Can it be possible that our passion for large cities, and large parties, and large theatres, and large churches, develops no faith nor hope nor love which would not find aliment and exercise in a little “world of our own”?” _The Brick Moon by Edward Everett Hale

At the beginning of the twentieth century, rocket pioneers started to explore the possibility of interplanetary travel and imagined huge platforms orbiting the Earth, a starting point for missions to the Moon and Mars. One of them was Konstantin Tsiolkovsky (1857-1935), a Russian and Soviet rocket scientist, who made significant contributions to rocket science and space research. He was the first to solve the problem of propelling a rocket against the force of gravity, and he also formulated the mathematical fundamentals of modern astronautics. (Konstantin E. Tsiolkovsky: The Father of Astronautics and Rocket Dynamics.’, n.d.)

Another pioneer was the German scientist Hermann Oberth (1894-), who is considered one of the founding fathers of rocketry and astronautics. Oberth developed the V-2 rocket for Nazi Germany during World War II and later helped launch the United States into space. In 1923, he published a book titled "The Rocket into Interplanetary Space," in which he discussed the technical feasibility of interplanetary travel and proposed the idea of a spaceship that could travel to other planets. (Tillman, 2013)

In the first decades of the 20th century, scientists dreamed of other worlds, but at the same time, they were trying to imagine what our planet might look like from space. Astronomers and weathermen, started applying art to their subjects of study to express their experiences and visions about Earth. In the 1930s, the French astronomer and artist Lucien Rudaux came closer than anyone else before in illustrating what the Earth looks like as a planet. His illustrations, with data taken from the world’s weather records, showed a planet surrounded by cloud systems.

Also in the 1930s, George W. Mindling, a weather expert and a poet who worked for the Weather Bureau and who authored several papers on weather forecasting and correlation studies, dreamed of observing weather systems from afar so they could view and predict storms moving over the surface of the earth. In his 1939 poem, titled The Raymete and the Future, Mindling predicted the use of infrared sensors and the launch of weather satellites, which came to fruition on April 1st, 1960 with the launch of TIROS I.

The Raymete and the Future

“Have you noticed how often in times that are past

We have used new inventions to improve the forecast?

Television is coming, it is not far away;

we’ll be using that too in a not distant day.

Photographs will be made by the infrared light

that will show us the clouds both by day and by night.

From an altitude high in the clear stratosphere

Will come pictures of storms raging far if not near

Revealing in detail across many States

the conditions of weather affecting our fates

There will then be no need for the stale weather maps

With their many blank spaces and wide open gaps

And with no information as the hours elapse.

In the coming perpetual vision to one show

we shall see the full action of storms as they go.

We shall watch them develop on far away seas,

and we'll plot out their courses with much greater ease”

In the late 1940s, only a few visionary scientists could appreciate the usefulness of orbiting weather satellites in providing valuable and accurate data to some of the most complicated meteorological phenomena, such as storms, hurricanes, and cold fronts. One of the first to consider the potential benefits of meteorological satellites for both warning people about approaching severe weather and gathering information about the atmosphere was Dr. Harry Wexler, director of meteorological research, at the U.S. Weather Bureau. In a 1956 address to the American Astronautical Society, Wexler said:

"Since the satellite will be the first vehicle contrived by man that will be entirely out of the influence of weather, it may at first glance appear rather startling that this same vehicle will introduce a revolutionary chapter in meteorological science--not only by improving global weather observing and forecasting, but by providing a better understanding of the atmosphere and its ways. There are many things that meteorologists do not know about the atmosphere, but one thing they are sure of is this—that the atmosphere is indivisible—that meteorological events occurring far away will ultimately affect local weather. This global aspect of meteorology lends itself admirably to an observation platform of truly global capability—the Earth satellite."

Wexler went so far as to commission a painting of what he thought the Earth would like from a satellite, taking into account Earth’s colours, the reflectivity of sunlight, and the various cloud types.

Then, on October 5, 1954, an Aerobee rocket, a scientific project that was initiated and supervised by James Van Allen and his colleagues at the University of Iowa, was launched from White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico, carrying two 16 mm movie cameras in its payload. The rocket was used to take photographs of the Earth's cloud patterns and was the first to capture the Earth in colour from space, but it also accidentally obtained pictures of a tropical cyclonic storm system near Del Rio, Texas. It was the first time that such a storm had been photographed from an altitude and the first time that the earth had been successfully photographed in its natural colour from rocket altitude.

The meteorologists got excited, and they tried to convince the politicians of the value of launching satellites into space. It wasn’t easy. Ed Pursell of Harvard and a member of the first President’s Science Advisory Committee (PSAC) had been recalling how he had to explain repeatedly in seminar talks all over Washington, why satellites did not simply fall straight towards the centre of the earth like a rock.

It was the 1950s, and although the Cold War tensions had been relaxed somewhat, largely owing to the death of the long-time Soviet dictator Stalin in 1953, the standoff remained. The rocketry projects of the U.S. and the Soviet Union evolved into independent but parallel paths. By the late 1950s, Chief Designer Sergey Pavlovich Korolev’s team produced R-7, (for the Russians P-7), the world’s first intercontinental ballistic missile. Using R-7, the Soviet Union launched the first Sputnik satellite on 4 October 1957. It was this development that convinced the politicians in the United States to move ahead with the development of satellites and space exploration.

The Killian report was presented to the National Security Council in February 1955 by Dr James R. Killian Jr., who was the director of the 42-member Technological Capabilities Panel of the Science Advisory Committee of the Office of Defense Mobilization, which was formed in response to a Presidential request that a study be made of U.S. technological capability to reduce the threat of surprise attack. (Report by the Technological Capabilities Panel of the Science Advisory Committee)

The Killian report was the beginning of the triumph of technology and the eclipse of old-fashioned espionage at the CIA. “… we can use the ultimate in science and technology to improve our intelligence take,” argued Killian and he urged Eisenhower to build spy planes and space satellites to soar over the Soviet Union and photograph its arsenals.

The technology was within America’s grasp. A memo sent by Loftus Becker, a lawyer who served as the deputy director for intelligence at the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) from January 1952 to April 1953, was proposing the development of a satellite vehicle with a television camera for reconnaissance, to survey the Soviet Union from deep space. The challenge was to develop the camera, but Edwin Land, a flamboyant genius and Harvard dropout, was sure he could do it. He had already invented the Polaroid.

In November 1954, Land and Killian met with the President Eisenhower to discuss high-altitude reconnaissance. The President approved the development of the U-2 spy plane (missile), a powered glider with a camera in its belly that would put American eyes behind the iron curtain. Eisenhower gave the go-ahead, along with a glum prediction. “Someday”, he said, “one of these machines is going to be caught, and then we’ll have a storm.”

Sources

Konstantin E. Tsiolkovsky: The Father of Astronautics and Rocket Dynamics.’. (n.d.). Retrieved from New Mexico Museum of Space History:

G. Mindling, “1939, NOAA Celebrates 200 years of Science, Service and Strewards”, Available from [http://celebrating200years.noaa.gov/events/tiros/welcome.html], NOAA (09 October 2007)

L.F. Hubert and Otto Berg, “A Rocket Portrait of a Tropical Storm”, Monthly Weather Review, 83 (June 1955), 119-120, American Meteorological Society

Allan Bromley, The President's Scientists: Reminiscences of a White House Science Advisor, Yale University Press, 1994.

James R. Killian, Sputnik, Science and Eisenhower: A Memoir of the first assistant to the President for Science and Technology, Cambridge, MA:MIT Press. 1967. Pp.70-71.