How the 1982 El Niño Changed Our World

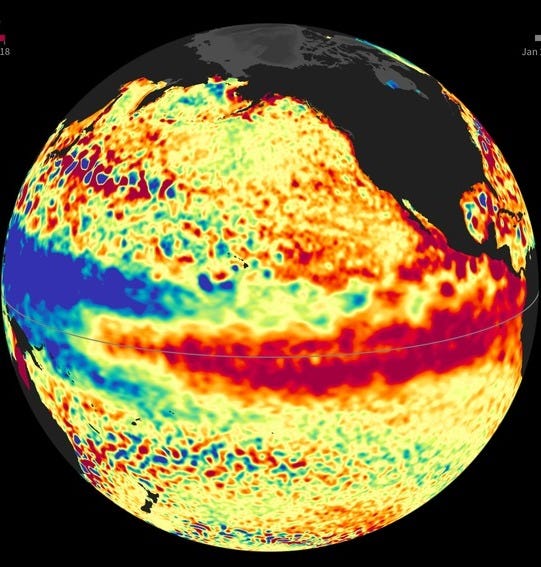

The 2024 annual sea surface temperature over the extra-polar oceans reached a record-breaking. How much did El Niño contribute to this record?

According to Copernicus Climate Change Service, the annual sea surface temperature (SST) over the extra-polar oceans reached a record-breaking 20.87°C. The year started with a strong El Niño, which later shifted to neutral conditions.

But how much did El Niño contribute to this record? While El Niño did boost global temperatures, the data show that the exceptionally high temperatures in 2023–2024 happened even though this El Niño was weaker than the major events of 1982–1983, 1997–1998, and 2015–2016.

To understand the magnitude of El Niño's impact, let’s go back to 1982—a year marked by one of the strongest and most devastating El Niño events in recorded history.

For centuries, fishermen in Paita, a bustling seaport on Peru’s northern coast, observed a curious phenomenon. Every few years, a warm current sweeps down from the north, briefly overriding the cool and nutrient-rich waters of the Humboldt Current (or Peru Current). This recurrent event known as the Corriente del Niño, or just El Niño (The Christ Child), usually made its appearance around Christmas, disrupting the marine ecosystem and leaving fishermen with empty nets.

El Niño occurs every three to four years, bringing exceptionally heavy rains and wreaking havoc on the fishing economies of Ecuador and Peru. They used to be a familiar, albeit disruptive, part of life. But by the mid-1970s scientists began to notice that something shifted on El Niño behaviour. Could human-induced climate change be playing a role?

1982 was not supposed to be an El Niño year. All the usual indicators, like sea-surface temperatures, looked normal, and if an El Niño were brewing, it should have announced itself months earlier. Instead, 1982 brought one of the most catastrophic El Niño events of the 20th century. It caused weather-related disasters on almost every continent. Australia, Africa, and Indonesia suffered droughts, dust storms, and wildfires. There was widespread flooding across the southern United States, lack of snow in the northern United States, and an anomalously warm winter across much of the mid-latitude regions of North America and Eurasia. (Quiroz, 1983) During that period, trade winds not only collapsed--they reversed.

In the eastern tropical Pacific, sea-surface temperatures soared by a shocking 5°C above average, and Peru and Ecuador experienced record-setting rainfall, extensive flooding and landsliding. On the other side of the Pacific, Hurricane Iwa (it means Thief) struck the Hawaiian Islands, producing widespread power failures and destruction. It was the twelfth and final hurricane of that season capping off a year of freak weather.(Williams, 2015)

The 1982 El Nino killed about 2,000 people around the world and caused a dramatic collapse of the fish stocks at the coasts of Peru. The global economic impact, initially estimated at $8 billion, was later recalculated to a staggering $4.1 trillion. Some meteorologists have tied El Niño to above-normal temperatures recorded in Alaska and northwestern Canada - and reduced salmon harvests.

But perhaps the most striking effect of the 1982-1983 El Niño came from an unlikely source. David Salstein and Richard Rosten of Atmospheric and Environmental Research, Inc. in Cambridge, Massachusetts found that the angular momentum of Earth shifted slightly as a result of changes in the normal pattern of the jet stream and trade winds. In late January 1983 Earth’s days stretched by an extra 0.2 milliseconds. (Amaral, n.d.)

The 1982–83 El Niño reshaped our understanding our understanding of Earth’s interconnected systems. It was a reminder that, in nature, even the smallest shifts can ripple across the globe with staggering consequences.

This article is free to read, but if you found it useful, please consider subscribing or making a small donation at my Buy Me A Coffee page below. The Climate Historian is an independent publication, entirely supported by readers like you.

Sources and References:

Amaral, K. (n.d.). El Niño and the Southern Oscillation:. doi: https://www.whoi.edu/science/B/people/kamaral/ElNino.html#82-83

Quiroz, R. S. (1983). The Climate of the "El Niño - Winter of 1982-83 - A Season of Extraordinary Climatic Anomalies . Monthly Weather Review., 111(8), 1685-1706.

Williams, J. (2015, June 12). How the super El Nino of 1982-83 kept itself a secret. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/capital-weather-gang/wp/2015/06/12/how-the-super-el-nino-of-1982-83-kept-itself-a-secret/