The Emergence of Climate Politics

Tracing the Roots of Modern Environmental Policy

Economic Growth as Progress

In the aftermath of World War II, economic recovery and industrial expansion were at the forefront of government agendas worldwide. In the minds of many people, economic growth and technological advances became synonymous with progress. Rising living standards, new consumer products, and an ever-expanding infrastructure brought about a new sense of optimism and possibility. Many people, especially in Western societies, began to view continuous economic growth and increasing prosperity as natural outcomes of human progress. In the words of Herbert Spenser, progress was not an accident but a necessity.

Yet, this relentless march toward growth came at a cost. The industries that powered this economic growth relied heavily on fossil fuels—oil, gas and coal. They were cheap, abundant, and efficient, but they were also extremely harmful to the environment. Their rampant consumption during this period led to a steep increase in greenhouse gas emissions and the climate crisis we face today.

In the 1960s, a series of environmental disasters sparked public awareness about the natural environment, and scientists began raising the alarm over pollution, deforestation, and biodiversity loss. Influential works like Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (1962) exposed the devastating effects of pesticides, particularly DDT, and other chemical substances.

The same year in London, seven hundred fifty people died in the “pea soup” fog attributed to air pollution and in 1967, the Torrey Canyon oil tanker spilled millions of litres of oil in the English Channel. In the Sahel, bordering the southern Sahara, a devastating five-year drought from the late sixties into the early seventies led to famine and widespread death across the continent (Sen, 1983). And Japan mourned the 2,265 victims of mercury poisoning caused by a chemical company releasing the toxin into Minamata Bay. The site would lend its name to Minamata disease, the neurological disease caused by mercury poisoning.

Yet, these early environmental disasters were secondary to the immediate rewards of economic growth. Economists from the neoclassical tradition were aware that massive resource consumption presented sustainability challenges but assumed that, once a resource became scarce, technology would conveniently step in to substitute scarce inputs. Meanwhile, for many policymakers, the promise of quick economic gains overshadowed the distant but growing environmental risks.

The Awakening

But in the 1970s the idea of continuous progress was losing much of the fascination it had had for earlier generations. The great idea of progress had by then been exposed as fiction. The concept of 'progress' has often been used to justify the dominance of the free market, enabling colonial exploitation of non-Western societies and leading to significant harm to our planet's biosphere. The first Earth Day in 1970, led by U.S. Senator Gaylord Nelson, marked the first tentative step towards environmental consciousness. Millions of Americans took to the streets, demanding action showing that environmental issues could no longer be ignored.

An increasing number of academic studies warned that, if current practices persist, humans risk a gradual degradation of their living conditions—and, worse, humankind may irreparably damage Earth’s ability to support life.

What followed was a painfully slow awakening to a crisis that was growing more urgent with every passing year. Gradually the environment and climate began to move from the fringes of political conversation to the centre stage – though not without their share of drama, resistance, and denial.

Only One Earth

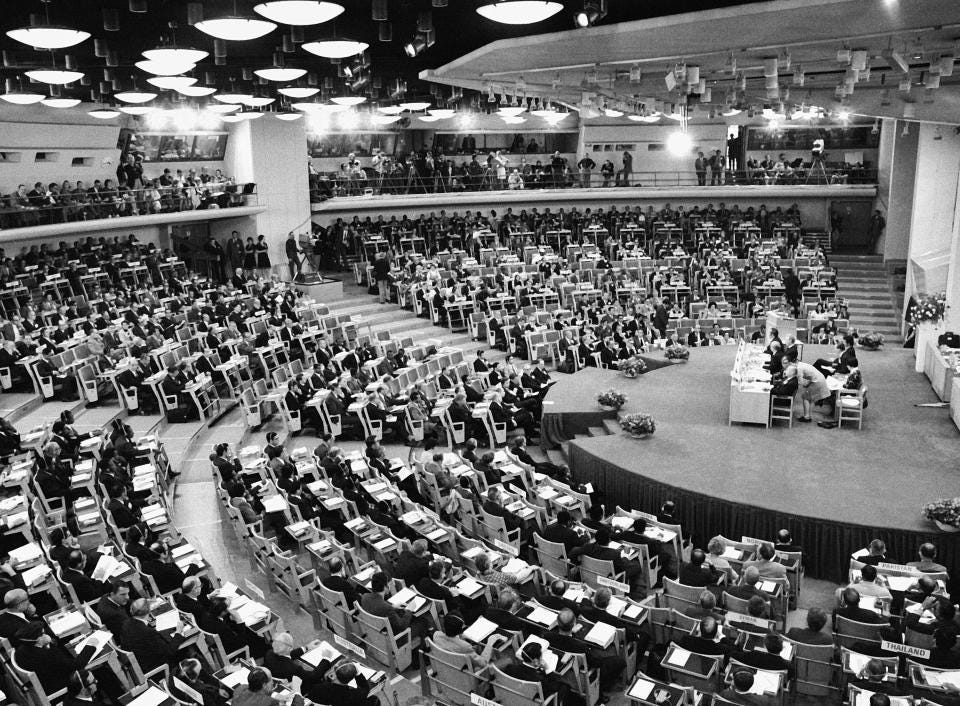

The year was 1972. Confronting with the stark reality that human activities were having a profound impact on the planet, delegates from 114 nations gathered that June in Stockholm for an unprecedented event—the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment (UNCHE).

The primary objective of this summit was to address the alarming environmental global challenges such as pollution, deforestation, and biodiversity loss. But it also marked the beginning of a debate that would shape environmental diplomacy for decades to come. Could environmental protection and economic growth coexist? The debate still continues with strong arguments on both sides.

In his opening speech, Swedish Prime Minister Olaf Palme openly criticised the industrialised world for its ecological and economic exploitation, stating that these actions were causing the world’s greatest environmental problems at the expense of developing countries.

The opening speech of Olaf Palme at the Stockholm Conference (1972)

Tensions in the conference run high. For developed countries, there was concern that the conference could be turned into a platform for developing nations to extract financial support, particularly from nations with colonial histories like the United Kingdom and France. Meanwhile, developing countries, eager for economic growth, viewed potential environmental regulations with caution, fearing that such measures could hinder their progress and development.

Yet, the conference achieved a remarkable consensus with the Stockholm Declaration, establishing a set of 26 principles that would lay the foundation for modern environmental governance. The First Principle states:

“Man has the fundamental right to freedom, equality and adequate conditions of life, in an environment of a quality that permits a life of dignity and well-being, and he bears a solemn responsibility to protect and improve the environment for present and future generations. In this respect, policies promoting or perpetuating apartheid, racial segregation, discrimination, colonial and other forms of oppression and foreign domination stand condemned and must be eliminated.”

It represented a new mode of thinking, making a shift from viewing the environment as merely a resource to be exploited to recognising it as essential to human well-being and societal progress. This new perspective laid the groundwork for modern environmental law and policy, merging environmental protection with economic growth and social equity. In essence, it evolved to become a more comprehensive framework that will give rise to the concept of sustainable development, which the landmark Our Common Future report—often called the Brundtland Report—brought to the world stage.

But that’s a story for another day. The question now is: where did climate change fit into these early discussions?

Climate Change Takes the World Stage

While climate change wasn’t a priority at the Stockholm conference, it was beginning to gain traction as scientific research advanced and its effects became more apparent. Slowly a grim reality emerged: climate change was no longer a distant threat but a rapidly unfolding crisis, reshaping economies, environments, and lives across the globe.

Even as evidence accumulated, climate change remained a divisive topic. Interestingly, from the 1940s through the 1970s, the world experienced a cooling period – a phenomenon largely due to sulphate aerosols released during the post-war industrial expansion. These particles reflected sunlight, temporarily cooling the Earth’s surface. The 1963 eruption of Mount Agung also contributed by adding more aerosols, that slightly reduced global temperature between 1958 and 1965. (Hansen & et al, 1978) This led some scientists to speculate about the possibility of a new ice age, a subject that media headlines have eagerly sensationalised. This speculation was partly fuelled by a 1971 paper by climate scientist Stephen Schneider, then with NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. Schneider suggested that if industrial aerosol pollution levels continue to rise unchecked, they could, theoretically, trigger an ice age.

Later research would reveal that greenhouse gas-induced warming would surpass aerosol cooling effects, setting the planet on a trajectory towards rapid warming. But at the time the scientific debate was shaped by a complex interplay of factors, and many unknowns regarding the speed and the magnitude of the impacts of climate change.

For politicians, this new science was a challenge. Climate science intersected with politics in complex ways. In the early 1980s, it had been connected with opposition to the Reagan administration’s nuclear weapons policy. Scientists led by space scientist Carl Sagan had warned against a “nuclear winter” if atomic weapons were ever used. Sagan, a co-author of the influential “TTAPS” report, underscored the grim potential for severe, global-scale disruptions to climate—even if from a different angle. (Turco, Toon, T.P. Ackerman, Pollack, & Sagan, 1990)

As awareness of climate risks grew, the U.S. House of Representatives led by Representative Al Gore held several hearings on rising levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide. However, despite the efforts to build consensus, substantial action remained elusive. For some, whether cold or hot it was premature to forecast a dire future given the limited understanding of climate science at the time. (Lambright, 2006)

Villach 1985: The Quiet Alpine Meeting That Changed Climate Politics Forever

The turning point came in 1985, at a meeting in the small town of Villach in the Austrian Alps. The gathering, chaired by the renowned meteorologist Bert Bolin, brought together a small group of climate scientists who until then were working in relative isolation within their own fields to discuss and assess a phenomenon that while not yet fully understood, had begun to loom ominously over the future—human-induced climate change.[1]

For several days, these scientists pored over emerging data, debated evidence and reached an alarming conclusion: climate change was accelerated and immediate action was required. In their concluding statement, the Villach group boldly announced that "in the first half of the next century a rise of global mean temperature could occur which would be greater than any in man's history” [2] ((WMO), (UNEP), & (ICSU), 1986)

"Suddenly the climate change issue became much more urgent," recalls Bert Bolin, one of the central figures in the climate-change debate, who supervised the meeting's scientific report. The scientists called, of course, for more research. However, the Villach report also took a decisive stance, emphasizing that "the rate and degree of future warming could be profoundly affected by governmental policies," and urged policymakers to take action. This little-known meeting in Villach marked a turning point in the climate debate. It was the first time scientists took on the role of advocates, issuing a clear warning that political action was as vital as scientific research in addressing the climate crisis.

In an interview with the BBC in 2014, environmental scientist Jill Jäger recalled that she left the meeting with a feeling that “something big is happening […] the big adventure here was bringing all the pieces together and get this complete picture and we can see that the changes are coming much faster.” (Climate Change: the Early Years, 2014)

This little-known meeting marked a crucial point. Climate scientists began stepping out of the lab and into the political arena, setting the stage for a decades-long debate that would continue to shape climate policy. Their call for urgent action led to the formation of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in 1988, laying the groundwork for global efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

[1] These invitational meetings began in 1980 under the influence of Dr Mostafa Kamal Tolba, an Egyptian scientist who served for seventeen years as the Executive Director of the UNEP and sponsored by three international organizations – ICSU, UNEP and WMO - which joined forces to bring the threat of anthropogenic climate change onto the international policy agenda.

[2] Statement by the UNEP/WMO/ICSU International Conference on THE ASSESSMENT OF THE ROLE OF CARBON DIOXIDE AND OF OTHER GREENHOUSE GASES IN CLIMATE VARIATIONS AND ASSOCIATED IMPACTS, http://www.icsu-scope.org/downloadpubs/scope29/statement.html

Sources and Further Reading

conference of the Assessment of the role of carbon dioxide and of other greenhouse gases in climate variations and associated impacts. Geneva: WMO. doi:https://library.wmo.int/records/item/28228-report-of-the-international-conference-of-the-assessment-of-the-role-of-carbon-dioxide-and-of-other-greenhouse-gases-in-climate-variations-and-associated-impacts

Baker, L., Shaffrey, L., & Hawkins, E. (2021). Has the risk of a 1976 north-west European summer drought and heatwave event increased since the 1970s because of climate change? Quarterly Journal of Royal Meteorological Society. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.4172

Bell , B., & Cacciottolo, M. (2017, March 17). Torrey Canyon oil spill: The day the sea turned black. Retrieved from BBC: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-39223308

Bolin, Bert, et al., eds. (1986). The Greenhouse Effect, Climatic Change, and Ecosystems. SCOPE Report No. 29. Chichester: John Wiley.

Caviedes, C. N. (1975). El Niño 1972: Its Climatic, Ecological, Human, and Economic Implications. Geographical Review, 65(4), 493-507. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/213747

Chasek, P. (2020). Stockholm and the Birth of Environmental Diplomacy. IISD. doi:https://www.iisd.org/system/files/2020-09/still-one-earth-stockholm-diplomacy_0.pdf?q=sites/default/files/2020-09/still-one-earth-stockholm-diplomacy_0.pdf

(2014, October 9). Climate Change: the Early Years. BBC. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p027rh9c

Cook, K. H. (2008, October). The mysteries of Sahel droughts. Nature Geoscience, 1, 647-648. Retrieved from https://www.nature.com/articles/ngeo320

Lambright, W. (2006). NASA and the Environment: Science in a Political Context’ Paper presented for NASA Societal Impact Conference, Paper presented for NASA Societal Impact Conference

Pielke , R. A. (2000, April ). Policy history of the US Global Change Research Program: Part I. Administrative development. Global Environmental Change, 10(1), 9-25.

Sen, A. (1983). 'Drought and Famine in the Sahel', Poverty and Famines: An Essay on Entitlement and Deprivation. Oxford: Oxford Academic. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/0198284632.003.0008

UNEP. (1973). Report of the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment - Stockholm, 5-16 June 1972. New York: UN. doi:https://wedocs.unep.org/handle/20.500.11822/30829

United Nations. (1972). Declaration of the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment. Stockholm. Retrieved from https://www.ipcc.ch/apps/njlite/srex/njlite_download.php?id=6471

White, R. M. (1979). Climate at the Millenium. Proceedings of the World Climate Conference: A Conference of Experts on Climate and Mankind.