The Forgotten Genius Who Saw Climate Change Coming—Before Tyndall Did

Eunice Foote: A fascinating tale of science, feminism and greenhouse effect

August 23, 1856.

In a packed hall in Albany, New York, the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) convened for its annual meeting. The air buzzed with fierce debates— ideas clashing, egos soaring, and scientific discoveries unfolding.

And then something unexpected happened. A paper titled Circumstances Affecting the Heat of Sun’s Rays was presented. It was groundbreaking. Provocative. And years ahead of its time.

But the real shock?

The author was a woman.

Meet Eunice Newton Foote—scientist, inventor, and feminist. A woman whose name should be in every climate science textbook, yet history swept her under the rug. Until now This is a fascinating tale of science, feminism and climate change.

Eunice Foote (1819 -1888) was a woman ahead of her time. Born on a Connecticut farm in 1819, she had something many young women of her era did not: access to education. She attended the Troy Female Seminary, the first institution in the United States offering women an education comparable to men’s colleges.

The Troy Female Seminary has a history of its own. It was founded in 1821 by Emma Hart Willard, a pioneer of women's education, in Troy, New York. It had a rigorous curriculum —teaching math, science, history, and languages at a time when women’s education was confined to embroidery and etiquette.

Foote’s education was unconventional. So was she.

The Discovery That Changed Everything (And Should Have Changed History)

By the 1850s, Foote had married Elisha Foote, a patent lawyer, and settled in Seneca Falls, New York. While raising two daughters, she conducted scientific experiments in her homemade lab—because professional labs weren’t exactly welcoming to women.

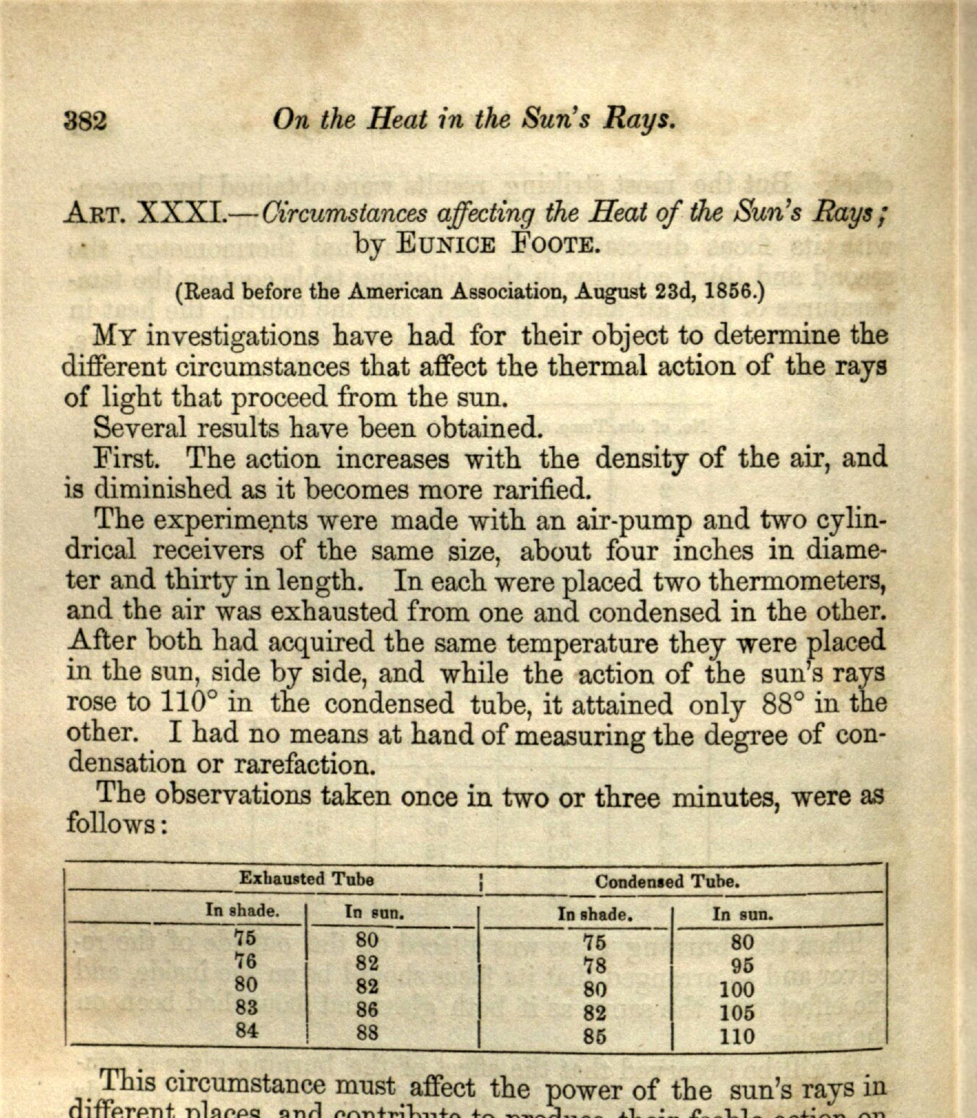

In the 1950s she started conducting experiments on carbon dioxide and heat. Using nothing more than glass cylinders, thermometers, and an air pump, Foote demonstrated that carbon dioxide (then called "carbonic acid gas") absorbed more heat from sunlight compared to other gases. This led her to conclude that

"An atmosphere of [carbon dioxide] would give to our earth a high temperature; and if, as some suppose, at one period of its history the air had mixed with it a larger proportion than at present, an increased temperature must have necessarily resulted."

If this sounds familiar, it is because it is. That is what would later be known as the greenhouse effect. Three years before John Tyndall’s famous experiments, Eunice Foote had already figured it out.

She wrote a paper and tried to present the results of her experiments at the 1856 meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. There was just one problem. Women weren’t allowed to present papers. Instead, a man – Professor Joseph Henry of the Smithsonian Institution, read her paper aloud.

Introducing Foote, Henry announced that

“… science was of no country and of no sex. The sphere of woman embraces not only the beautiful and the useful, but the true.”

Perhaps this was his attempt to shield Foote and her findings from sexist criticism or, worse, indifference. Unfortunately, “indifference” would be the best word to describe how her findings were received.

Neither Foote’s paper nor Henry’s reading made it into the official conference proceedings. Later the same year the paper was published in The American Journal of Art Science (Volume 22) but received little or no attention.

And then? Nothing. The name Eunice Foote has been erased from memory. In 1856, science wasn’t just about discoveries—it was about who made them.

The Rediscovery of Eunice Foote

For over a century, the scientific community credited John Tyndall as the first to demonstrate that water vapour and carbon dioxide absorb heat – one of the key ideas for understanding the greenhouse effect and climate change.

Yet, history has an uncanny way of revising itself, even if we have to wait about 150 years.

Foote’s groundbreaking discovery might have remained lost forever if it wasn’t for Raymond Sorenson, a geologist who collected old copies of the Annual of Scientific Discovery. He stumbled upon Henry’s presentation on Foote’s paper in the 1857 volume and immediately realised its significance. Eunice Foote had been the first to link carbon dioxide to climate change.

Why Didn’t She Get Credit?

The rediscovery of Foote’s paper also brought up another issue. The Irish physicist John Tyndall was credited with discovering the heat-absorbing properties of carbon dioxide and water vapour, although he made his discovery three years after Foote published her paper. Yet he failed to cite Foote’s work. Did he even know about Foote’s work?

Probably not. Science was slow to cross the Atlantic in the 1850s, and European institutions largely ignored American research—especially when it came from a woman conducting experiments in her home.

And yet, she did it. And her hypothesis was remarkably prescient. Foote was a woman in 19th-century America—an amateur scientist, yes, but a brilliant one. And while she had a keen scientific mind, she lacked something equally important: connections in the male-dominated world of academia.

John Tyndall, by contrast, was a professional scientist with access to the best equipment, elite institutions, and scientific journals. When he published similar findings in 1859, the world listened. Foote? Forgotten. We can only imagine what Foote would have succeeded if she could have Tyndall’s rigorous scientific training and expensive and precise equipment.

More Than a Scientist—A Feminist Trailblazer

Foote wasn’t just a scientist. She was a women’s rights activist. In 1848, she attended the historic Seneca Falls Convention, signing with 67 other women and 32 men, the Declaration of Sentiments— demanding equal rights for women in all spheres of life. She served on the editorial committee for the convention and worked alongside other prominent feminists like Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Elizabeth M'Clintock, Mary Ann M'Clintock, and Amy Post.

Eunice Foote fought for women’s education. She fought for women’s rights. She fought for a future where women’s ideas mattered.

Would She Be Proud of Today? Probably. But she’d also remind us that the fight isn’t over.

Because while history finally remembers Eunice Foote, women are still battling for recognition, funding, and respect.

And climate change? Well, we’re still arguing over that, too. Eunice Foote saw it coming 150 years ago. Maybe it’s time we listen.

This article is free to read, but if you found it useful, please consider subscribing or making a small donation at my Buy Me A Coffee page below. The Climate Historian is an independent publication, entirely supported by readers like you.

Notes:

Jackson, R. (2019, February 13). Eunice Foote, John Tyndall and a question of priority. (Royal Society)

Sorenson, R. (2011). Eunice Foote’s pioneering research on CO2 and climate warming. (Search and Discovery)

Wells, D. A. (1857). Heat of the Sun's Rays (Annual of Scientific Discovery, 159-161)

It's certainly true that Ms. Foote was maltreated by the culture of the time. However, Ms. Foote's conclusion was not supported by her evidence. She demonstrated that carbon dioxide absorbs some solar radiation. She did NOT demonstrate that CO2 absorbs the outgoing infrared radiation from the earth's surface -- the primary process causing the earth's surface temperatures to rise. I explained this crucial distinction in an essay to which I linked in a previous comment. Did you not read that essay? If so, I will be happy to explain in greater detail any points that I failed to make clear.

Thank you for sharing this gem!