Behind the Tear

Few campaigns in the annals of American advertising have left as indelible a mark as the 1971 "The Crying Indian" advertisement. Yet, what appeared to be a sincere call for environmental responsibility was, in reality, a sophisticated exercise in corporate deflection.

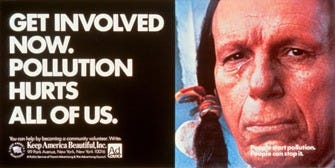

Picture this: A Native American man, called Iron Eyes Cody, paddles his canoe through pristine waters. As he approaches the shore, the landscape transforms into a polluted wasteland. He disembarks, only to have a bag of trash tossed carelessly at his feet by a passing car. The camera zooms in on his face, capturing a single tear rolling down his cheek. This image, burned into the collective memory of millions of Americans, became the face of the anti-litter movement. But like most things in advertising, not everything was as it seemed. And sometimes, even the most convincing tears are just glycerine and good acting.

You see, Iron Eyes Cody was about as Native American as a slice of pizza Margherita. The man shedding a tear for the Earth was actually an Italian-American actor born Espera Oscar de Corti, who made a career out of portraying Native Americans in Hollywood. The deception, however, didn’t end with the actor’s background. Behind this emotional plea was "Keep America Beautiful," an organisation funded by none other than the corporations responsible for creating the very litter they condemned—beer bottlers, can makers, and soda producers.

Rather than addressing their own practices, companies like Coca-Cola, PepsiCo, and American Can Company were deflecting blame for environmental pollution onto individuals. Their message was simple. Environmental protection is not the industry’s responsibility. It wasn’t about regulating the industry. It was about YOU remembering not to toss your gum wrapper on the sidewalk. Basically, it was environmental gaslighting at its finest.

The advertisement promoted the catchline, ‘People Start Pollution. People Can Stop It,’ and won awards. The campaign made it onto Ad Age Magazine’s list of the top 100 advertising campaigns of the 20th century. It remained popular, until quite recently, when, in a fitting epilogue, the rights to the ad were transferred to the National Congress of American Indians. Their plan? To retire the ad permanently, acknowledging that it was "inappropriate then and remains inappropriate today".

Deflection as a strategy

The individualization of responsibility didn’t start with the Crying Indian ad, but that campaign captured perfectly a tactic that has become pervasive across industries. Large corporations have long mastered the art of deflection, steering the conversation away from necessary policies or regulatory changes that threaten their profits, even when their products or practices pose threats to the people and the planet. Instead, they place the burden on individuals, urging consumers to change their habits and behaviours.

This strategy is particularly well-documented in the U.S., with two of the most notorious examples being the tobacco industry and the gun lobby, both of which have successfully promoted the idea of personal responsibility as a smokescreen to fend off stricter regulation.

Blame the Smoker, Not the Smoke

In the mid-20th century, as evidence mounted linking smoking to lung cancer, the tobacco industry didn’t just fight back—they mastered the art of deflection. Instead of outright denying the dangers, they funded research to stir doubt, muddying the scientific waters.

In the 1950s, the Tobacco Institute launched its “health reassurance" campaigns. These campaigns framed smoking as a lifestyle choice, not a public health crisis, deflecting blame from the product to the individual. With this strategy of producing scientific uncertainty and casting smoking as a personal responsibility issue, the industry successfully evaded regulation for decades.

This strategy—creating doubt and shifting responsibility—became a blueprint for other industries facing inconvenient truths, from climate change to pollution. Their message: the problem isn’t the product; it’s the person using it.

Guns Don’t Kill, People Do—And Other NRA Myths

The National Rifle Association (NRA) and the broader gun lobby have used similar strategies, particularly since the 1970s, to deflect attention away from the role of firearms in gun violence. The NRA portrays gun violence as a problem rooted in individual behaviour rather than the accessibility of guns. Their slogan "guns don’t kill people, people kill people," has turned what could have been a conversation about gun regulation into one about personal responsibility.

The NRA's focus on individual responsibility has been paired with advocacy for self-defence and gun ownership as fundamental rights- a rhetorical strategy that has been remarkably effective in reshaping the public debate. From glossy ads showing mothers defending their homes to speeches celebrating the Second Amendment as the cornerstone of American liberty, the NRA has skilfully redirected the debate from gun control to the individual's right to bear arms.

But what gets lost in this narrative is the profound effect guns have on how people perceive the world. Guns aren’t neutral tools; they are designed for quick, decisive, and often deadly action. The simple presence of a firearm transforms everyday situations. Take, for instance, an argument in a parking lot. Without a weapon, it’s just two people having a heated exchange. Add a gun, and suddenly, it becomes something else entirely—a moment with potentially deadly consequences.

Deflection Comes to Climate Change: We Are All Guilty

The redirection of responsibility from corporations to individuals stands as one of the most masterful corporate manoeuvres. It paved the way for what would become a pervasive strategy in the years to come: the individualization of responsibility. Nowhere has this tactic been more fully realised than in the fossil fuel industry. By positioning climate change as an issue of individual behaviour—whether it is our dietary habits, the light bulbs we use, or how often we drive or fly—fossil fuel corporations have obscured their role in environmental destruction.

This narrative creates a convenient illusion: that climate change can be solved through small personal sacrifices rather than meaningful policy reform and corporate accountability. Take, for example, the concept of “personal carbon footprint.” BP promoted the idea in the mid-2000s, launching one of the first personal carbon footprint calculators and asking individuals to calculate their own greenhouse gas emissions. The message was clear: the solution to climate change lies not in changing corporate behaviour, but in you choosing to turn off the lights when leaving the room. And while no one can argue that reducing personal emissions is unimportant, it’s the sheer audacity of the campaign that stands out.

This is the same BP that, in 2023 saw its carbon emissions climb for the first time since 2019, as the company started up new oil and gas projects and increased its production levels. That year the company's emissions reached 32.1 million metric tons of carbon dioxide, up 0.6 percent from 31.9 million tons recorded in 2022. BP also reported a 10% rise in its methane emissions (methane is a potent greenhouse gas) to 31,000 tons in 2023 from 28,000 tons in 2022, due primarily to increased flaring in its Azerbaijan-Georgia-Türkiye region and Tangguh operation.

BP wasn’t alone. Over the years, other fossil fuel giants like ExxonMobil and Shell followed suit, launching their own campaigns that encouraged individual energy-saving tips and recycling habits while they continued to emit vast amounts of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. At the same time, these companies were quietly funding climate misinformation, sowing doubt about the reality of climate change even as they publicly promoted corporate sustainability.

As Malcolm Harris wrote in New York Magazine, “There’s little doubt that fossil-fuels are, culturally speaking, on the wrong side of history. But there is still a lot more money to extract from those wells, and the fossil-fuel businesses are intent on extracting as much as they can. It’s not necessarily such a bad time to be an oil and gas company, in other words, but it is a bad time to look like one. These companies aren’t planning for a future without oil and gas, at least not anytime soon, but they want the public to think of them as part of a climate solution. In reality, they’re a problem trying to avoid being solved.”

Plastic: A Modern Paradox

The individualisation of responsibility doesn’t stop at carbon emissions; it extends to plastic waste, another problem closely linked to the fossil fuel industry. Plastics, mostly derived from oil and gas, have made major companies like ExxonMobil and Dow Chemical billions, thanks to the steady demand for single-use products. Plastic producers have known for more than 30 years that plastic recycling is neither economically viable nor technically feasible. Yet, this knowledge has not stopped them from perpetuating the myth of recycling as a solution.

As environmental awareness grew, ExxonMobil raised the stakes by pushing "chemical recycling"—a process that, in most cases, turns plastic into fuel rather than reusable products. This isn’t innovation; it’s a convenient way to keep the plastic production engine running. The stark reality is that only a small fraction—around 9%—of all plastic ever produced has actually been recycled.

But, instead of tackling the issue of plastic overproduction, these companies have shifted their focus on consumer behaviour. Sounds familiar? Much like the anti-littering campaigns of the past, they deflected responsibility to the consumers. It’s not their fault for overproducing plastic; it’s OUR fault for not recycling enough.

This framing serves to protect the interests of the fossil fuel and petrochemical industries. As renewable energy gains ground and the demand for fossil fuels declines, plastics have become an increasingly important market for fossil fuel companies. In fact, plastics are expected to drive fossil fuel demand in the coming decades. As such, reducing the production of plastic would directly impact the profitability of these industries.

Meanwhile, the growing mass of discarded plastic bottles has given rise to another great environmental crisis of our time—global plastic pollution. It’s no longer just littering. No place is safe from plastic pollution—from the depths of the Mariana Trench to the air we breathe. Microplastics have been found in lungs, placenta and breast milk. Research published in Science in 2020 showed that even the most isolated areas in the United States—national parks and national wilderness areas—accumulate microplastic particles after they are transported there by wind and rain.

A few weeks ago, in a landmark move, California Attorney General Rob Bonta has filed a lawsuit against ExxonMobil, accusing the company of misleading the public for decades about plastic recycling. The lawsuit, which follows a two-and-a-half-year investigation, claims that ExxonMobil has falsely promoted plastic recycling as a solution to pollution since the 1980s—despite knowing full well that most plastics are neither recyclable nor biodegradable.

What makes this lawsuit particularly significant is that it's the first of its kind—no state has ever sued a company for deceiving the public about plastic recycling. If successful, this could be a landmark case, holding corporations accountable for the true scale of the damage they cause and for climate deception.

This article is free to read, but if you found it interesting and would like to support my research and writing, please consider making a small donation at my Buy Me A Coffee page below:

Sources and Further Reading:

Brahney, J., & et al. (2020, June 12). Plastic rain in protected areas of the United States. Science, 368(6496), 1257-1260. doi:10.1126/science.aaz581

Brandt, A. (2012, January). Inventing conflicts of interest: a history of tobacco industry tactics. Am J Public Health., 102(1), 63-71. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2011.300292

Dauvergne, P. (2018). *The power of environmental norms: Marine plastic pollution and the politics of microbeads*. Environmental Politics, 27(4), 579–597. [DOI:10.1080/09644016.2018.1449090](https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09644016.2018.1449090)

Geyer, R., Jambeck, J. R., & Law, K. L. (2017). *Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made*. Science Advances, 3(7), e1700782. [DOI:10.1126/sciadv.1700782](https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.1700782)

Greenpeace (2021). *Plastic Recycling is a Dead-End Street—Year After Year, Plastic Recycling Declines Even as Plastic Waste Increases*. [Link] https://www.greenpeace.org/usa/news/plastic-recycling-is-a-dead-end-street-year-after-year-plastic-recycling-declines-even-as-plastic-waste-increases/

Harris, M. (2020, March 3). Shell is looking forward. New York Magazine. Retrieved from https://nymag.com/intelligencer/2020/03/shell-climate-change.html

Microplastics are everywhere — we need to understand how they affect human health . (2024). Nature Medicine, 30(913). doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-024-02968-x

Proctor, R. N. (2004). The Global Smoking Epidemic: A History and Status Report. Clinical Lung Cancer, 5(6), 371-376. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1525730411701899

Reuters. (2024, March 8). BP's carbon emissions rise for the first time since 2019. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/bps-operational-emissions-edge-higher-2023-2024-03-08/

Sant, V. W. (2022, May 5). The NRA’s Shadowy Supreme Court Lobbying Campaign. Politico. Retrieved from https://www.politico.com/interactives/2022/nra-supreme-court-gun-lobbying/

Stroud, A. (2020). Guns don’t kill people…: good guys and the legitimization of gun violence. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 7. Retrieved from https://www.nature.com/articles/s41599-020-00673-x

The Guardian. (2020). *Plastics industry knew recycling wouldn't work, reports reveal*. [Link](https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/sep/21/plastics-recycling-oil-industry)

Tang, t. (2023, February 27). Rights to Famous "Crying Indian" TV ad to go to Native American group, which is retiring it. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved from https://www.latimes.com/entertainment-arts/tv/story/2023-02-27/rights-crying-indian-anti-pollution-ad-native-american-group

ugh, AI art