The Origins of Climate Change

Svante Arrhenius: Quantifying the contribution of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere

Today we are going to go back in time and discover the fascinating origins of the science of climate change. It all started more than a century ago, in April 1896, when the Swedish scientist Svante Arrhenius published a paper in the Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science. Its title was “On the Influence of Carbonic Acid in the Air upon the Temperature of the Ground.” In this remarkable work, Arrhenius introduced the very first model exploring how what we now call carbon dioxide—then referred to as "carbonic acid"—could influence the Earth's surface temperature. It was a pioneering idea that would lay the foundation for modern climate science.

But before we talk about Arrhenius’ groundbreaking work and findings, let’s discover the man behind the science.

Svante August Arrhenius was born on his ancestor’s farm estate in Vik, Sweden on 19 February 1859. When he was one year old, his family moved to Uppsala where his father worked as a land surveyor for the University of Uppsala. Interested in mathematics from an early age, Svante studied at the Katedralskolan (The Cathedral School), one of the oldest institutions in Sweden, and in 1876, he entered the University of Uppsala to study mathematics, chemistry and physics.

Electrolytic Theory of Dissociation

After completing his degree, a young and curious Arrhenius went to Stockholm to work under Professor Erik Edlund, whose research was concentrated on the theory of electricity and the electromotive forces generated when two different metals are put in contact. But young Arrhenius’ interests lay elsewhere. While Edlund was fascinated by metals, Arrhenius was more intrigued by liquids—specifically, how electric currents moved through solutions. He soon shifted his focus to electrolytic solutions and began to explore a bold idea: what if chemical reactions were caused by tiny, electrically charged particles or ions? These particles carried electric charges even when there was no current flowing through the solution. These ions could, therefore, transmit an electric current.

Arrhenius wasn’t starting from scratch. Decades earlier, another Swedish chemist, Berzelius, who is considered one of the founders of modern chemistry, has arrived at the conclusion that there is a connection between electricity and chemistry. But his ideas had been all but forgotten and Arrhenius’ new way of approaching the study of electrolytes was considered a bit too revolutionary by the chemists of the time. [1]

When in 1884, Arrhenius presented his groundbreaking Ph.D. thesis, Investigations on the Galvanic Conductivity of Electrolytes, his examiners thought his ideas were too radical and gave him the lowest passing grade possible. Nearly twenty years later, in 1903, Arrhenius would prove them all wrong—becoming the third-ever recipient of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his groundbreaking theory of electrolytic dissociation. [2]

So, by 1884, Arrhenius had some big ideas but not many prospects. Fortunately, he was awarded a travel stipend by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences and for the next six years, he visited several European institutions, doing postdoctoral research. His first stop was Riga, where he worked with Wilhelm Ostwald, a rising star in physical chemistry. Then he went to Würzburg to work with Friedrich Kohlrausch and from there to Graz where he worked with Ludwig Boltzmann, whose work in thermodynamics deeply influenced Arrhenius’s thinking. His last stop was Amsterdam, where he crossed paths with Henry van ‘t Hoff —who would later win the very first Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

Throughout this academic journey, Arrhenius did more than just learn—he shared. He discussed his theory of electrolytic dissociation with anyone who would listen and slowly but surely, he began to win followers and build a network of supporters across Europe. His persistence had paid off, and in 1891 he was finally offered a position as a lecturer at the University of Stockholm.

Quantifying the contribution of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere

At around the same time, in the late 19th century Sofia Rudbeck was breaking barriers. She was one of the first women in Sweden to earn a doctorate in science and the very first woman admitted to the Swedish Geological Society. She was also one of Svante Arrhenius’s first female students—and soon, much more than that. In 1894, they married in Uppsala, but their marriage was short-lived. Just two years later, it ended in divorce. While the breakdown of his marriage in 1896 was personally devastating for Arrhenius, it also marked a turning point in his work—and the history of climate science.

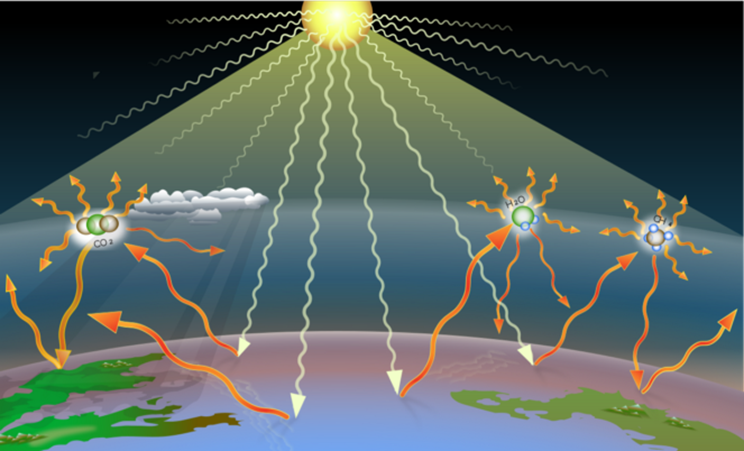

That same year in April 1896, Svante Arrhenius published a paper in the Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science, titled On the Influence of Carbonic Acid in the Air upon the Temperature of the Ground. In this paper, he presented the first-ever model of how carbon dioxide in the atmosphere affects Earth’s temperature – a concept we now know as the greenhouse effect. [3]

The main question that Arrhenius sought to answer in his article was: “Is the mean temperature of the ground in any way influenced by the presence of heat-absorbing gases in the atmosphere?” He cited John Tyndall, whose work on the atmosphere’s role in trapping heat, Arrhenius thought was of great importance, as well as Claude Pouillet, who studied how carbon dioxide absorbs heat and of course, Joseph Fourier, the French scientist, who compared the Earth’s atmosphere to a hothouse—letting sunlight in but trapping heat. He also drew heavily from his colleague Arvid G. Högbom, a geologist whose research was concentrated on the pre-Cambrian period, igneous rocks, ores, glacial, and geomorphological problems.

So, in the late 19th century, long before supercomputers and climate models, Svante Arrhenius took on a massive challenge—to figure out how carbon dioxide in the atmosphere affects the Earth’s temperature. Compared to modern climate models, which are enormously complex, Arrhenius’ model was incredibly simple. He didn’t have satellites, advanced sensors, or data sets. Instead, he relied on pen, paper, and sheer determination.

He had to make a few assumptions – ignoring things that today we consider as crucial like, for example, clouds and atmospheric or oceanic circulations. [4] But despite these simplifications, his understanding of how the Earth absorbs and radiates heat was remarkably accurate. Arrhenius showed that changes in the amount of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere could alter the Earth’s heat balance—and its temperature. He even suggested that these changes might explain dramatic shifts in climate, like the Ice Ages.

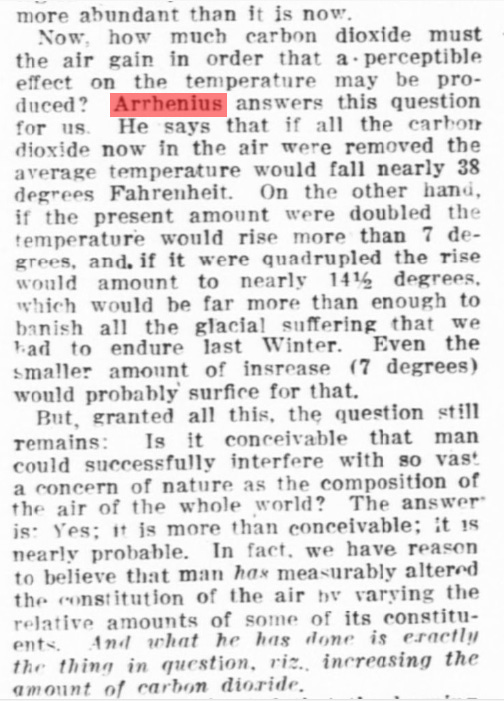

Arrhenius did 10,000 to 100,000 calculations by hand to work it all out. No computers, no shortcuts—just math. And here’s the mind-blowing part – he concluded that if we were to double the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere, global temperatures could rise by 5 to 6 degrees Celsius.

In his words, “if the quantity of carbonic acid increases in geometric progression, the augmentation of the temperature will increase nearly in arithmetic progression.” In plain English, this means that if we double the carbon dioxide concentration in the atmosphere, the temperature will increase by a set number of degrees.

He estimated that doubling the amount of carbon dioxide would take about 500 years and lead to a temperature rise of around 4 degrees Celsius. This prediction was based on the industrial activity of his time. Arrhenius couldn’t possibly imagine the wild increase in human activity and industrialization that followed in the 20th century.

Arrhenius’ ideas weren’t exactly welcomed by his peers in the Physics Society. Even Högbom, who had been open to the idea of carbon dioxide, as the cause of geological climatic change, now sided with those who believed that changes in the position of Earth’s poles—not greenhouse gases—explained climate changes in the past.

Despite the skepticism, Arrhenius’s ideas did make headlines, like this 1918 article from The Washington Times, which speculated on the impact of rising carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere. But Arrhenius wasn’t worried. In fact, he was optimistic. He believed that rising carbon dioxide levels might be a good thing, especially for colder parts of the world.

In his 1908 book, Worlds of the Making, he writes:

"By the influence of the increasing percentage of carbonic acid in the atmosphere, we may hope to enjoy ages with more equable and better climates… for the benefit of rapidly propagating mankind."

But Arrhenius thought we had thousands of years before we’d face any serious consequences. What couldn’t he have predicted was the explosive growth of industry, technology, and fossil fuel consumption in the 20th and 21st centuries. Instead of thousands of years, it’s taken less than 100 years after his death on 2nd October 1927 for his warnings to become our reality.

This article is free to read, but if you found it useful, please consider subscribing or making a small donation at my Buy Me A Coffee page below. The Climate Historian is an independent publication, entirely supported by readers like you.

References

Svante Arrhenius, On the Influence of Carbonic Acid in the Air upon the Temperature of the Ground, (The London, Edinburgh and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science, 5th series, April 1896)

S. Arrhenius, Worlds in the Making: The evolution of the Universe, (New York: Harper and Harper, 1908)

Crawford, E. (1998). Arrhenius '1996 model of the Greenhouse Effect in Context. In H. Rodhe, C. Robert, & C. Elisabeth, The Legacy of Svante Arrhenius: Understanding the Greenhouse effect. 276: Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

Slingo, A. (1998). Assessing the Treatment of Radiation in Climate Models. In H. Rodhe, & C. Robert, The Legacy of Svante Arrhenius: Understanding the Greenhouse Effect. Stockholm: Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

The Washington Times (Washington [D.C.]), August 25, 1918, (NATIONAL EDITION, American Weekly) https://www.loc.gov/resource/sn84026749/1918-08-25/

Notes

[1] In Sweden, Berzelius Day is celebrated on 20 August in honour of him.

[2] Faraday had worked out two laws describing electrolysis. 1) The amount of chemical change during electrolysis is proportional to the charge passed. 2) The charge required to deposit or liberate a mass m is given by Q = Fmz/M, where F is the Faraday constant, z is the charge of the ion, and M is the relative ionic mass. Faraday had spoken of "ions" (Greek- wanderer) as charged particles that carried electricity through solutions However, in the late 19th century, the nature of ions remained unclear. From his results, Arrhenius concluded that electrolytes, when dissolved in water, become to varying degrees split or dissociated into electrically opposite positive and negative ions. The degree to which this dissociation occurred depended above all on the nature of the substance and its concentration in the solution – being more developed the greater the dilution. The ions were supposed to be the carriers of the electric current, e.g. in electrolysis, but also of the chemical activity. The relation between the actual number of ions and their number at great dilution (when all the molecules were dissociated) gave a quantity of special interest (“activity constant”). Source: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/chemistry/1903/arrhenius/biographical/

[3] As it was common back then, the paper was written in English and German, the two major scientific languages of his time. The German article, titled Ueber den Einfluss des Atmosphärischen Kohlensäurengehalts auf die Temperatur der Erdoberfläche, was published in the Proceedings of the Royal Swedish Academy of Science in Stockholm, (Arrhenius, Ueber den Einfluss des Atmosphärischen Kohlensäurengehalts auf die Temperatur der Erdoberfläche, 1896)

[4] Nowadays, modern climate models are enormously more complex and are used in ambitious programs for analysing and predicting climate change.