The Science of Peace

In 1957, nearly 30,000 scientists from around the world came together to understand the only home we all share: Earth.

In the summer of 1957, as Cold War tensions kept the world in fear, and distrust dominated public relations, something quietly radical happened.

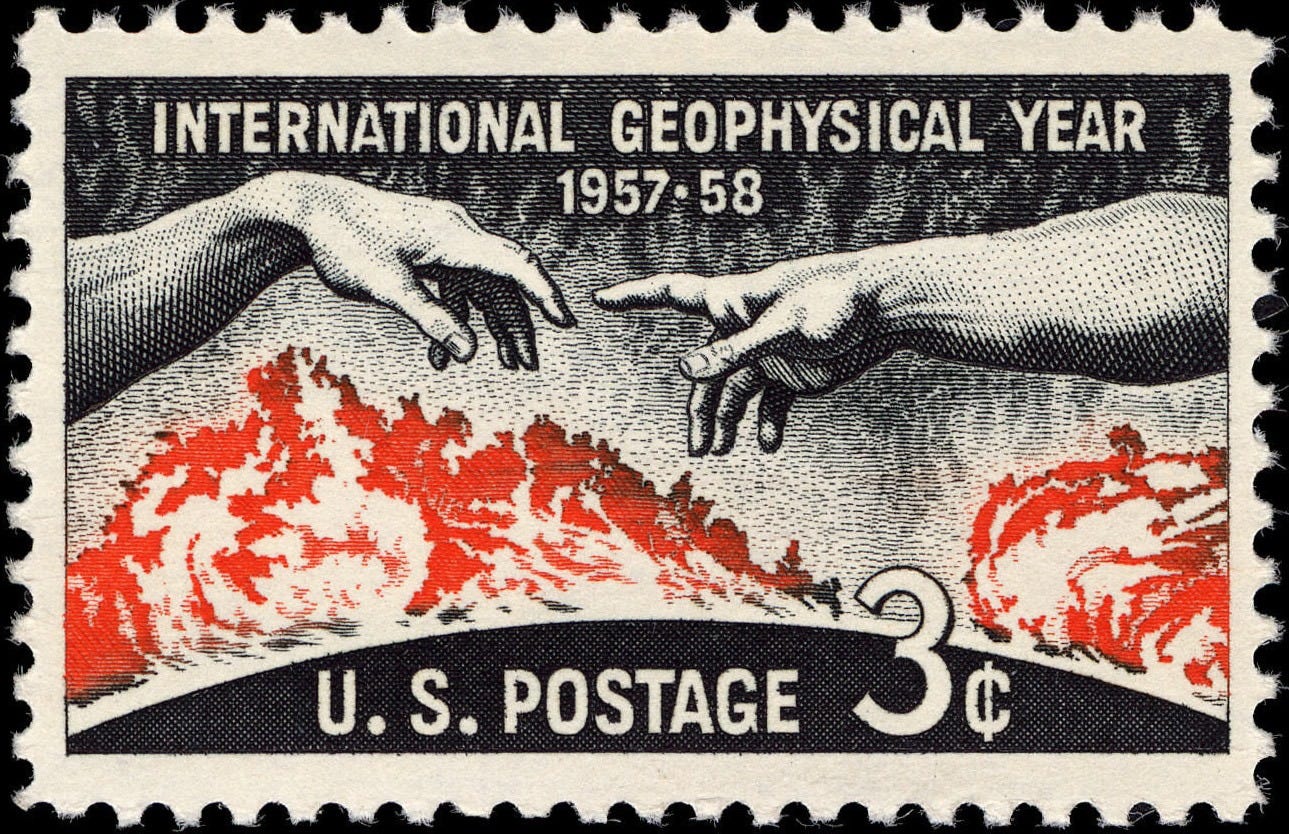

They called it the International Geophysical Year, or IGY, and it remains one of the most profound examples of scientific cooperation in human history. For 18 months, from July 1957 to the end of 1958, nearly 30,000 researchers from 67 countries, joined forces to study the only home we all share: Earth.

Sponsored by the International Council of Scientific Unions, the IGY covered an ambitious range of fields – from upper atmospheric physics and ocean currents to glaciology, seismology, and even the structure of Earth itself. It was science on a planetary scale, carried out with a commitment to open collaboration and the free exchange of knowledge.

In a radio and television address on June 30, 1957, President Eisenhower said that "the most important result of the International Geophysical Year is that demonstration of the ability of peoples of all nations to work together harmoniously for the common good. I hope this can become common practice in other fields of human endeavor."

Then came Sputnik. The Soviet Union’s historic launch of the first artificial satellite marked the dawn of the Space Age. Although the USSR had been part of the IGY, it placed limits on data sharing, particularly in space science. The ripple effects were profound. The United States increased funding for its space program, viewing expanded capabilities in space as vital to national prestige and strategic defense. Just months later, it launched Explorer 1, which made its own mark by discovering the Van Allen Radiation Belts, invisible shields that protect Earth from deadly solar winds.

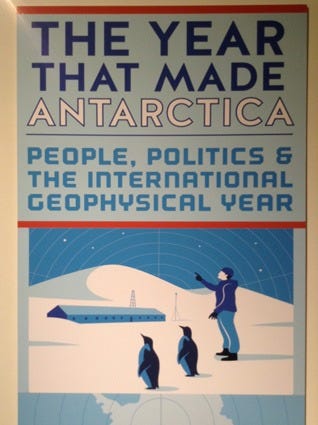

But it was Antarctica that emerged as one of the focal points of the IGY. It was during that time that the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station was established. The scientists in these research outposts braved some of the harshest environments on Earth to gather seismic, meteorological, and glaciological data. Their work was so successful that laid the foundation for the Antarctic Treaty of 1959, which to this day preserves the continent for peaceful collaboration and scientific discovery.

The IGY wasn’t just another event, it was the first time in history that the entire planet became a laboratory. The scientists involved didn’t just gather data, they redefined our understanding of the planet.

Its influence can be felt in today’s Earth observation programs, environmental treaties, and global scientific organizations. It directly inspired:

The International Geosphere-Biosphere Programme (IGBP) in 1987

The development of World Data Centres that allowed full and open access to the scientific data

The creation of long-term baseline atmospheric datasets, including early carbon dioxide measurements (e.g., the Keeling Curve)

It also helped pioneer the era of “big science,” where collaborative, multidisciplinary efforts paved the way for projects like the Hubble Space Telescope, CERN, and the International Space Station.

But perhaps the IGY’s greatest legacy may simply be that is that it happened at all. In a world fractured by ideological divides and deep suspicion, science emerged as a unifying force. Knowledge and data were shared freely. Scientists crossed borders without needing to check their flags at the door.

Could something like that happen today? I don’t know.

Today, science is often entangled in politics. Scientific funding is subject to political shifts. Data sharing is often restricted, filtered or delayed. Misinformation spreads faster than facts. Cooperation competes with competition.

And yet, there is something that hasn’t changed. No single nation can fully understand our planetary system. No single ideology can capture the complexity of our changing climate. And no border can stop rising seas or global pandemics.

The IGY reminds us of what it is possible when humanity chooses cooperation over division, when we listen and dare to build a future not on fear but on curiosity and shared knowledge.

Sources:

History of U. S.- Soviet Cooperation in Space U.S.-Soviet Cooperation in Space (Part 5 of 11)

International Geophysical Year (IGY) | Eisenhower Presidential Library

Wilson, John W. The International Geophysical Year. Harper & Brothers, 1961.

National Academy of Sciences. International Geophysical Year Overview

65 Years Ago: The International Geophysical Year Begins - NASA

James R. Fleming, Fixing the Sky: The Checkered History of Weather and Climate Control. Columbia University Press, 2010.

Thank you for this! I am an old lady, and this was unknown ancient history to me. I appreciate learning about the IGY, and am so terribly sad about how awry things appear to have gone… but it did establish some amazing precedents!

The parallel you drew to today’s fragmented scientific landscape really stood out.

Thank you for sharing such a hopeful and deeply thought provoking reflection on what’s possible when we choose collaboration over division.